TOKYO, Jan 22 — Japan has halted the restart of the world’s largest nuclear power plant just hours after it began, though the reactor remains “stable,” the operator said.

PETALING JAYA, Dec 9 — Is Malaysia a dua darjat (two-tier) society where ikan yu (big fish) and ikan bilis (small fry) in corruption cases receive different treatment from the Attorney General?

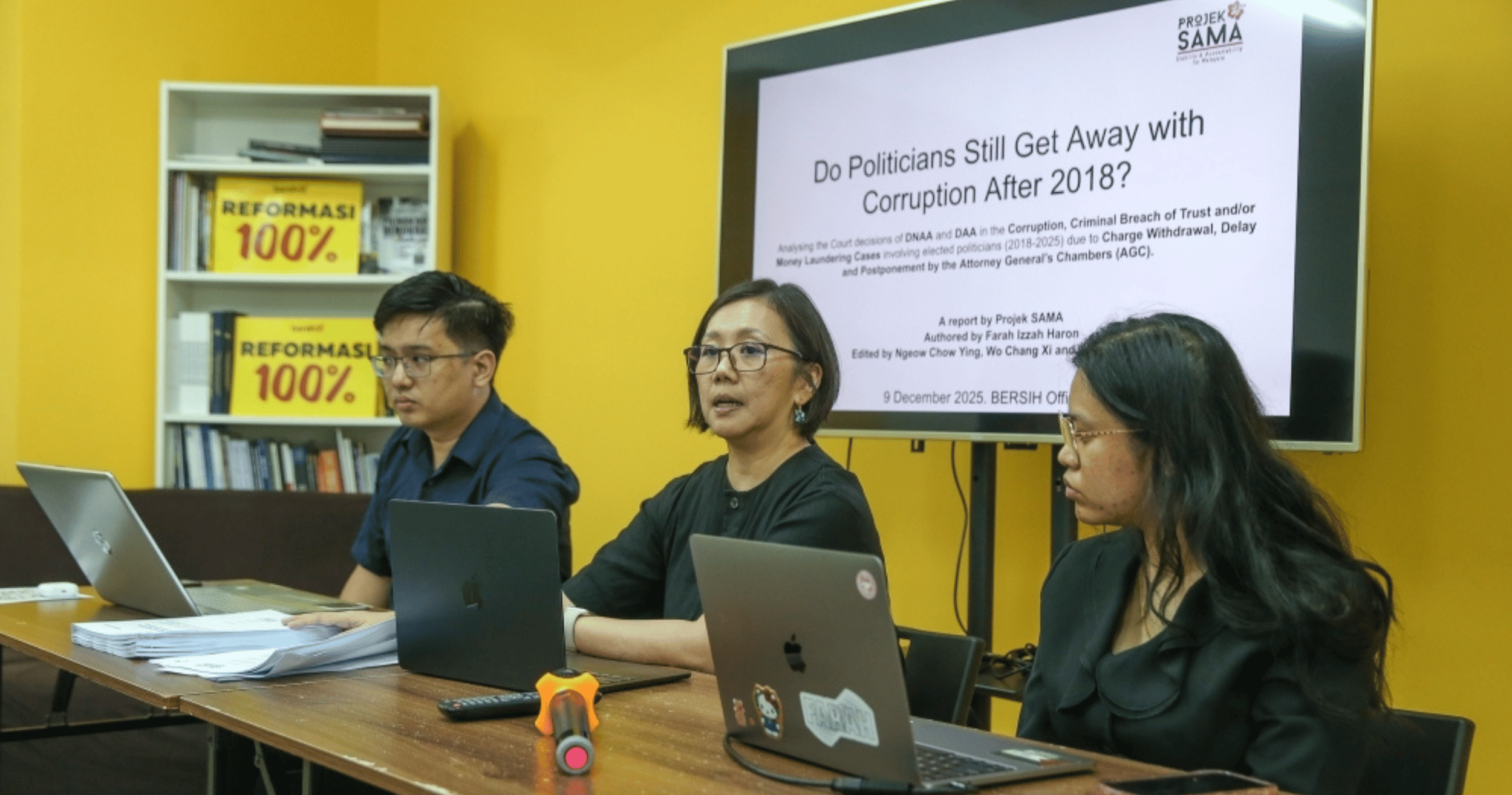

This was the central question that prompted non-governmental organisation Project Stability and Accountability for Malaysia (Projek SAMA) to conduct a study, with its findings released today in a report titled “Do politicians still get away with corruption after 2018?”

In its report, Projek SAMA noted that Malaysians have long perceived that politically connected individuals often evade conviction or severe punishment due to their power, wealth or alignment with those in власти. While the 2018 change of government raised public hopes that selective impunity would end, the group said prosecutorial decisions — including applications for discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA) involving several senior politicians linked to the ruling government — have since eroded confidence in the rule of law.

The study examined 28 cases involving 21 current and former lawmakers charged with corruption, criminal breach of trust and money laundering that were initiated or continued after the May 2018 general election.

When asked whether the findings confirmed the existence of a dua darjat justice system, Projek SAMA convenor Ngeow Chow Ying said it was for Malaysians to decide based on the data presented.

“We are not drawing any specific conclusion. We are laying down the facts and allowing readers to make their own judgment,” she told the media at the report’s launch at electoral reform group BERSIH’s office here.

Responding to questions on the Attorney General’s exercise of prosecutorial discretion in halting high-profile cases, Ngeow said the group was not making definitive conclusions due to the limited dataset.

“Out of the 28 cases, only 10 were discontinued midway. Three of those had legitimate reasons. We are simply presenting the facts surrounding each case,” she said.

The 10 cases involved politicians from across the political divide, including Lim Guan Eng, Tun Musa Aman, Datuk Nasharudin Mat Isa, Datuk Seri Tengku Adnan Tengku Mansor, Datuk Noor Ehsanuddin Mohd Harun Narrashid, Datuk Seri Ahmad Maslan, Datuk Seri Abdul Azeez Abdul Rahim, Tan Sri Shahrir Abdul Samad, Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi and Tun Daim Zainuddin.

Projek SAMA legal researcher Farah Izzah Haron said three cases were discontinued for legitimate reasons: Tun Daim’s case due to his death, Ahmad Maslan’s after settlement through a compound, and the DNAA for two charges against Datuk Mohammad Lan Allani to allow the charges to be refiled in the correct court.

Under Section 254 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the Attorney General, as public prosecutor, has the discretion to discontinue a prosecution, leaving the court to grant either an acquittal or a DNAA. Projek SAMA highlighted that once such a decision is made, the court has no power to compel the continuation of the case or to question the AG’s decision.

The organisation said its research focuses specifically on how prosecutorial powers are exercised in high-profile corruption cases.

For now, Projek SAMA will continue monitoring ongoing and future corruption cases involving politicians to determine whether a clear trend emerges.

“Our concern is the lack of transparency and consistency in prosecutorial conduct,” Ngeow said, citing cases where appeals were withdrawn following changes in government.

“When decisions are made without clear justification or public accountability, it undermines public trust. Confidence in the administration of justice is crucial to the legitimacy of any government, and that is why this report is important,” she added.

The 36-page report, written by Farah and edited by Ngeow, alongside Projek SAMA members Wo Chang Xi and Prof Wong Chin Huat, will be published on the organisation’s website.

It carries two key recommendations: reforming Malaysia’s prosecutorial structure and oversight, and enhancing transparency through political financing reform.